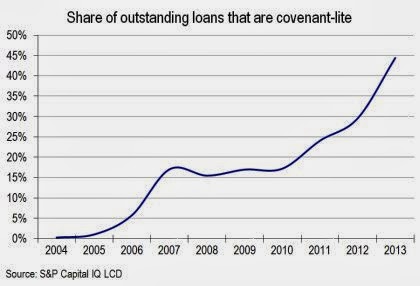

Covenant-light loans are on the rise

By Sober Look

The demand for corporate leveraged loans from both institutional and retail investors (described here) continues to stay unusually strong. Senior loan closed-end funds, BDCs, CLOs, hedge funds and even insurance firms are clamoring for senior loans of sub-investment-grade companies. Some view this asset class as one of the few “taper-proof” fixed income products because of the floating rate coupon and low default rates. Loan issuance has spiked this year to meet all the demand – in some cases at the expense of the high yield bond market.

| Source: Deutsche Bank |

The higher demand for this product is helping to gradually increase leverage of buyout transactions (see chart). But a more alarming trend is the sharp relaxation of lending terms – the so-called “cov-lite” (covenant-light) deals. Over 70% of recent deals for example have been structured as covenant-lite.

| Source: Deutsche Bank |

And according to LCD, these types of loans now represent nearly 45% of outstanding loans – a number that is significantly higher than during the LBO boom of 2007.

|

| Source: LCD |

US regulators have taken notice of the situation and are trying to get US banks to cut back on cov-lite transactions.

Bloomberg: – The Federal Reserve and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency sent letters to some of the biggest U.S. banks asking them to avoid arranging debt that may be classified by regulators as having some deficiency that may result in a loss, according to nine people with knowledge of the communication.

Regulators are seeking to cut down on excessive risk taking as typical lender protections have been stripped from credit agreements at a record pace. Speculative-grade borrowers have raised $239.6 billion of covenant-light loans this year, more than double the amount in 2012, Bloomberg data show. The LSTA, whose almost 350 members consist of banks, investors and corporate law firms, said the regulators’ request will hurt the least-creditworthy companies.

…

Covenant-light loans give companies more leeway to avoid a default as they don’t contain financial-maintenance provisions requiring the borrower to meet such restrictions as a set level of debt relative to earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization.

However banks tend to hold very little of this debt and therefore have little incentive to tighten covenants. They structure, syndicate, and collect fees, while the risk moves somewhere else. Many argue that weak covenants don’t matter when corporate default rates are as low as they have been recently. Haven’t we heard similar arguments in 2006 with another asset class?

Comments are closed.