My constant end of cycle worries

Despite my seemingly panglossian ‘cautiously optimistic’ post last week, I am still very much worried that we are hitting the end of this cycle. I’ll tell you why below. But, let me add just a few notes on style first! In keeping with ‘the Credit Writedowns style’ for 2020, this post will be brief. Also, it’s outside the paywall. Since I intend to write more, every fourth or fifth post is going outside the paywall. That way, people get a sense of what’s on offer.

Last ‘End of cycle or mid-cycle slowdown’ debate

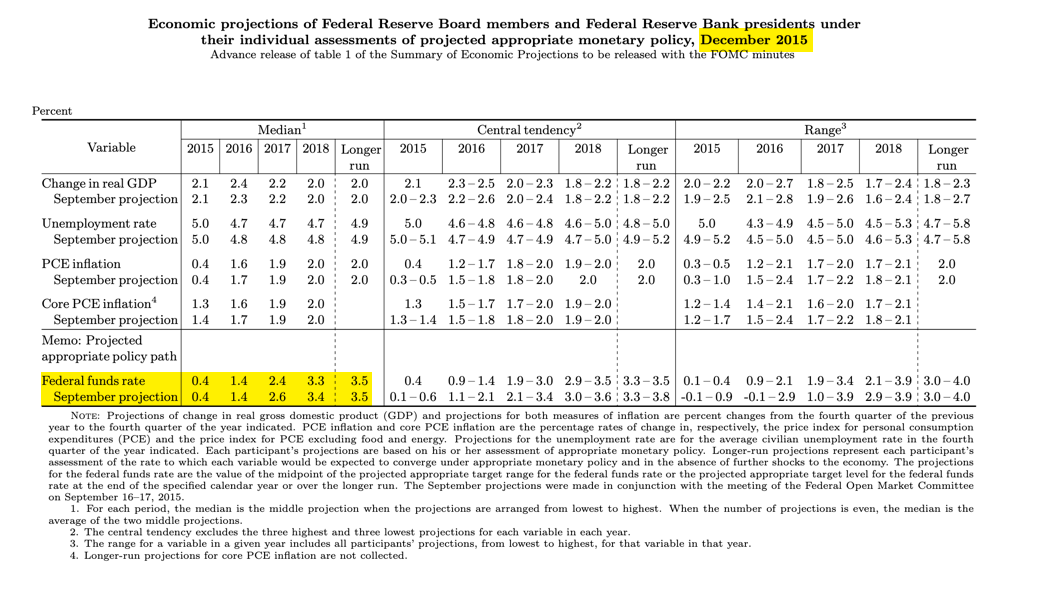

Back in the Yellen Fed days in 2015, I was also concerned about end of cycle dynamics. Let me set the scene here. If you recall, we got the tapering of asset purchases and the so-called taper tantrum in 2013. So, the Fed was reluctant to start raising rates pretty abruptly.

Despite the convulsions from the taper, in 2014, some Fed officials like Richard Fisher were calling for more action. His argument was that there was “substantial combustible fuel” from all of the quantitative easing the Fed had already done. And since the economy was recovered, there was no better time to hike rates. What’s more, the whole Phillips Curve view of the economy dominated thought inside the Fed. And according to that thinking, unemployment was already low enough to ignite inflation.

But the likes of Jerome Powell argued for caution:

In December 2014 the immediate issue was whether to start describing the Fed as “patient” in approving that first rate hike. But in approving the use of the word, then-Fed Gov. Jerome Powell and others said the bias should remain toward waiting, a position that has shaped Powell’s tenure as head of the central bank since early 2018.

“The very difficult mistake to recover from would be to go too soon,” Powell said in comments that show his evolution from a centrist Republican and outspoken deficit hawk to a central banker ready to keep rates on hold until inflation proves it is a problem, allowing workers to bank wage and job gains in the meantime.

Powell’s view led the day as the likes of Lael Brainerd and Jim Bullard joined him in voting with Janet Yellen to proceed with caution in 2014. Only in December 2015 did the Fed start the rate hike train. And remember, the train was supposed to gain speed pretty quickly – with rate hikes of a full percentage point every year.

But almost immediately, the Fed was stopped out by the shale oil bust. And the Fed paused for a full year before getting back on course in December 2016.

This ‘End of cycle or mid-cycle slowdown’ debate

Back in 2016, the big issue was a catastrophic fall in capital spending in the energy sector leaking into the rest of the economy and pulling the whole economy down. The fact that the Fed stood down and the economy recovered makes people more sanguine about the prospects that we are again seeing another mid-cycle slowdown, not an end of cycle decline. After all, the Fed not only stood pat this time, it cut rates three times.

The difference here is the labor market. As I wrote last week, almost all the labor market data shows a rolling-over since late 2018. I mentioned initial claims, non-farm payrolls and average hourly earnings last week. They show rate of change tops in September 2018, January 2019 and February 2019 respectively. So that’s a year during which the labor market has been decelerating along three major fronts.

This morning, I also saw that Dion Rabouin of Axios noted that Friday’s JOLTS data show the exact same pattern:

There were two themes that persisted in November’s U.S. job openings and labor turnover survey (JOLTS) released on Friday — the stubborn quits rate and the consistent decline in the number of job openings.

The big picture: Job openings fell by 561,000 to 6.8 million, the Labor Department said, the biggest drop since August 2015. That pushed the number of job openings to the lowest level since February 2018.

- The number of job openings in the U.S. peaked in November 2018 and has fallen almost every month since, with the pace of the decline picking up steam toward the end of the year.

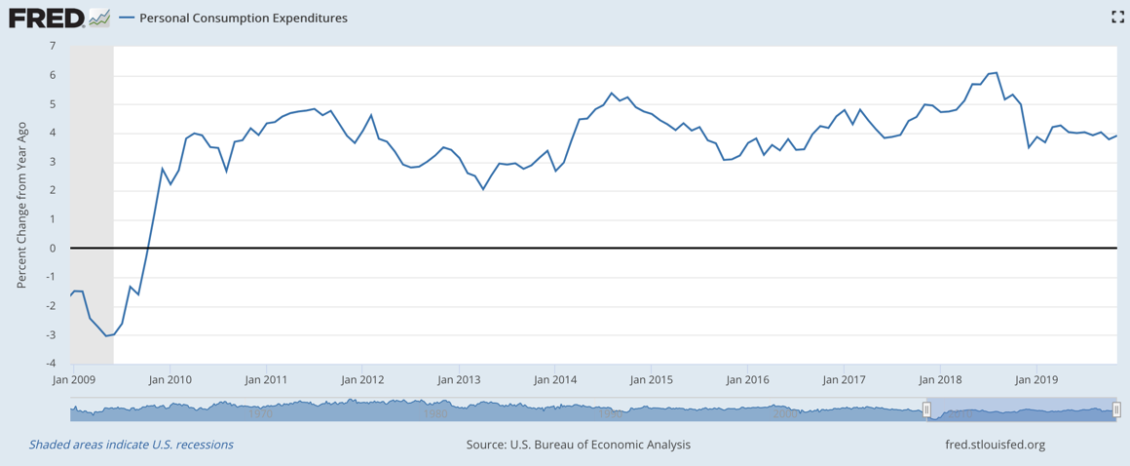

My takeaway here is that the JOLTS data confirm an ‘end of cycle’ pattern in the labor market: fewer hires, increased fires, lower wage growth. For this to be truly end of cycle though, it has to go on long enough to crimp consumption growth enough to tip the economy, which it really hasn’t done yet. Personal consumption expenditure growth has declined though.

There was a sharp decline from over 6% in nominal y-o-y growth in August 2018 to 3.5% in December. And without investigating it, I reckon that initial drop was tax-cut related. Since then PCE growth has been flat, with the latest figures showing just below 4% on a nominal basis through November 2019.

My take

If we dip toward the 3% range in personal consumption expenditures, I would become extremely worried about the end of cycle. For now, just remember two things. One, the macro figures do not foretell a near-term recession. They show at worst a slowing of growth. Second, the labor market has shown across the board slowing for over a year’s time. That is long enough to feed through negatively into consumption growth. And so I do expect the 4% PCE figure to decline toward the 3% range.

But let’s wait and see as the year progresses. The labor market slowing has end of cycle hallmarks. Nevertheless, a recession isn’t baked in by any means. That’s why, for now, I am cautiously optimistic about 2020.

Comments are closed.