What is pro-cyclical fiscal policy?

Economists often point out that the government can offset large falls or rises in private spending growth. This can prevent a depression using deficits when private sector spending and output is collapsing. But it can also be a stabilizing force that prevents the economy from overheating.But sometimes, governments mimic the private sector and amplify the trend in the economy. Economists call this pro-cyclicality. In worst case scenarios, pro-cyclicality is quite destabilizing.

Debt deflation and liquidity

This term ‘pro-cyclical’ got a lot of buzz after the financial crisis and during the European sovereign debt crisis. In both cases, private sector demand growth was collapsing. There was a lot of fear that these crises could end up in another Great Depression. So, the question was about arresting the fall. Students of economic history pointed to American economist Irving Fisher, who described debt deflation as the cause of the depression.

Fisher said that depressions happen due to collapsing asset values. Debtors trying to raise cash must sell at knock-down prices, triggering successive waves of defaults. The first drop in asset values triggers distress for enough debtors that their asset sales to raise cash cause a further drop in asset prices. They then sell whatever they can to raise cash, often their best and most liquid assets. Thus, the original asset deflation infects other asset classes, triggering distress in those sectors. And that ushers in more selling pressure and a bigger asset price collapse.

Unless someone steps in to arrest the fall in asset prices, banks that hold the defaulted loans as assets end up bankrupt, setting off a debt deflation within the heart of the financial system, deepening the crisis. In the 1930s, this is exactly what happened in the United States. The result was widespread bank failures, job losses and an economic Depression of unparalleled depth. During the financial crisis a decade ago, Ben Bernanke, as chairman of the Federal Reserve, successfully spearheaded the effort to arrest the debt deflation, not without significant controversy surrounding the methods employed.

Anti-cyclical fiscal policy

But in early 2009, the US economy was still in tatters and private sector growth was in free-fall. This is where pro-cyclicality comes into play. As the private sector collapses, so too do tax receipts, even as government expenses rise to deal with the increased unemployment and economic distress. In short, private sector distress creates budget deficits — and in the case of the US in 2009, where the percentage loss in unemployment was the largest in 60 years, the deficits were huge. If one were to act pro-cyclically and target the deficit, cutting spending and raising taxes, that would amplify distress in the private sector and perhaps precipitate debt deflation. Acting anti-cyclically and allowing deficits to rise transfers money to the private sector that decreases distress.

In the US case, deficits increased significantly and remained high until about 2013 or 2014.

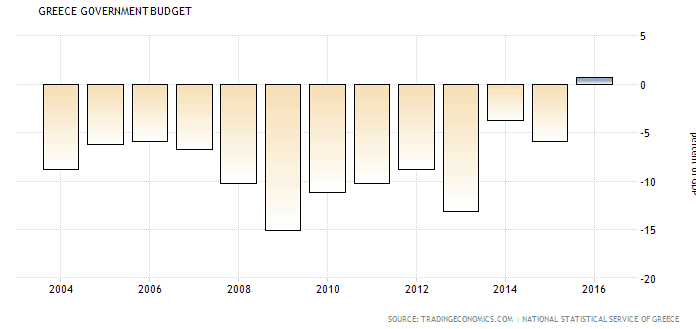

In Europe, by contrast, Greece, which is not a sovereign currency issuer, did not have the fiscal space to increase deficits when it ran into trouble after the initial global recession. The EU, IMF and ECB forced it to undergo austerity after 2010. And although deficits receded initially, documents leaked soon afterwards acknowledged that the planned “expansionary fiscal consolidation” had failed. Moreover, in the end, this pro-cyclical fiscal policy did indeed set off a debt deflation that increased deficits as the private sector collapsed and helped cause a Great Depression-sized loss in economic output.

Trump’s pro-cyclical fiscal policy

Things are very different now, as the world has begun a synchronized acceleration in economic growth. In the US, where the Trump Administration is trying to deliver the beginning of what it says should be consistent long-term growth of 3-4%, it is using deficit spending to get there. Irrespective of the composition of those deficits, the key question now is the timing, because this is pro-cyclical fiscal policy.

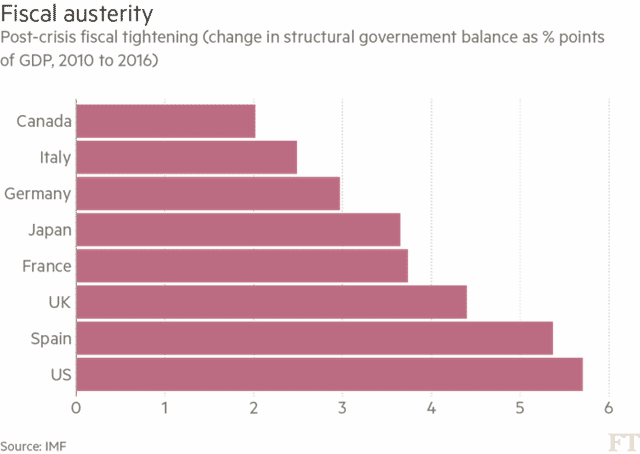

During the Obama Administration, there was a reduction in the structural budget deficit of 6% of GDP from 2010-2016.

Source: International Monetary Fund, The Financial Times

Now the pendulum is swinging the other way. And the economy is just hitting its stride. The right question to ask is whether these deficits will cause overheating.

That’s the big macro debate among market economists right now. Everyone is positive about the future prospects for the US economy. But what does this mean for inflation given the fresh stimulus from deficit spending? Stimulus should be medicine to nurse a sick economy back to health. Taking that same medicine when the illness appears to have passed will have very different effects on the patient.

Inflation?

Now if it means higher inflation, this inflation could be transitory, in which case it could reasonably be ignored. At the same time, in the near-term what matters is how the Federal Reserve reacts. If the Fed sees the inflation and believes it could be “embedded”, it might decide on pre-emptive rate hikes. And if it does, the potential for slowdown and recession will rise as speculative and Ponzi borrowers get caught out.

Keynesian and left-leaning economists are mostly against this abrupt policy shift. That’s both because the deficits redistribute income upwards and because the timing is very late in the business cycle. After all, a lot of Keynes’ appeal was about anti-cyclical fiscal policy. Even so, had the new Trump deficits been created to shore up America’s infrastructure or increase working-class wages instead of to give tax cuts to corporations, praise might have been more bipartisan. For Republicans, the expediency of pleasing donors and boosting growth ahead of the midterms was key in doing more deficit spending.

Nevertheless, the real test here is about inflation and the Fed. With Jerome Powell, a new Federal Reserve Chairman at the helm, there is a lot of uncertainty. If the Fed reacts with the same caution it has so far, long-term interest rates will remain low. And that could allow for continued growth in the economy and in corporate earnings, which ultimately helps stocks too. But since pro-cyclical policy amplifies the business cycle, it could cause overheating. if inflation rises or the Fed becomes more aggressive, the Trump Administration’s stimulus could boomerang. That would mean an initial bump in growth is followed by a steep fall. And the pain would spread beyond asset markets, to the real economy too.

Comments are closed.