The transformation of China as marginal buyer of last resort to exporter of deflation worldwide

I know the title of this post has a somewhat alarmist feel to it. However, I think it is the title that best describes the biggest macro theme now unfolding in the global economy. I have been in Grand Canyon country in the southwest of the US for the past week and have had the opportunity to pretty much unplug. Doing so has given me perspective in terms of what I am seeing on the macro side. And China’s role in the world is the most important theme that has emerged for me. A few notes on this below

Before I went on holiday last week, I was writing about the middling recovery in the US and how policy divergence was setting up struggles for emerging markets, energy high yield and commodities producers. I think this is only part of the story, however. The bigger part of the story comes not from the supply side but from the demand side. And to understand that, one needs to look at China.

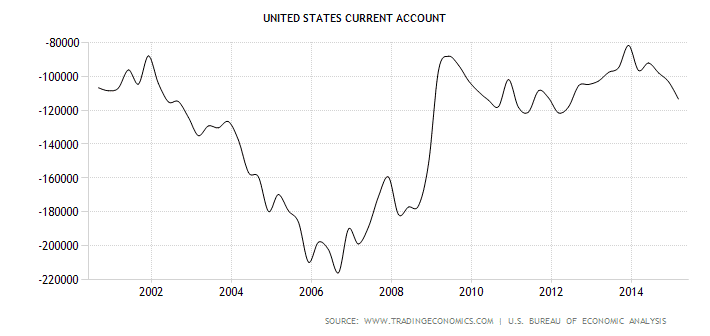

When the global economy turned down in late 2007, the US was forced to abdicate its position as the marginal buyer of last resort. While the US runs a current account deficit almost as a matter of course due to the US dollar’s position as the world’s major reserve currency that other countries need to accumulate, there was an enormous increase in US current account deficits in the period leading up to the crisis despite US dollar weakness. In the new millennium, the US consumer had become the marginal buyer of first and last resort. Then all of that went into reverse when the subprime crisis metastasized into a global economic crisis. In the charts below, you can see this.

China picked up the slack. The Chinese became the new marginal buyer of last resort.

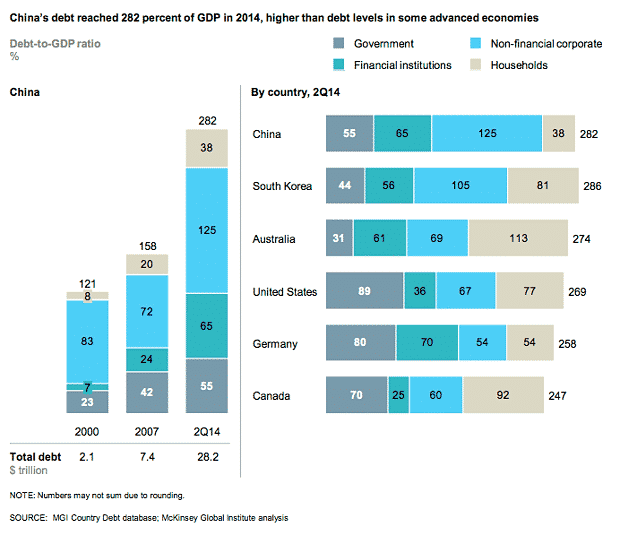

Government stimulus led the way as the Chinese government tried to maintain growth targets in the face of slumping external demand. But the stimulus was funnelled into the private sector, resulting in a huge increase in private non-financial debt, particularly property loans where the largest 4 banks have $364 billion of exposure on the books. The country’s overall debt levels quadruped in the seven years from 2007, taking debt to 282% of GDP.

Everybody benefitted. What this meant for the global economy was a floor under commodity prices in particular. If you look at the news from late 2008, for example, China was asking commodity producers to cut price to 1994 levels, more than 80% below recent highs. If this had continued, the carnage would have been immense. But China stepped up the stimulus and prices rebounded, as did the global economy. Not that all this buying by China meant that the excess supply had gone away. For example, by 2012, iron ore stocks were at record highs.

In the meantime, the benefit for emerging markets in particular was huge. These countries piled on debt, often via corporate borrowers funding in US dollars due to low US interest rates. There are $9 trillion of US dollar debt by entities outside the US, with emerging market share doubling since the Lehman crisis to half the total amount. Overall, global debt levels are $57 trillion, 40% higher than at the time of the crisis. While the growth in government debt has been the greatest, both corporate and household debt is on the rise. And only in the former housing bubble economies of the US, UK, Ireland and Spain have households in the OECD deleveraged.

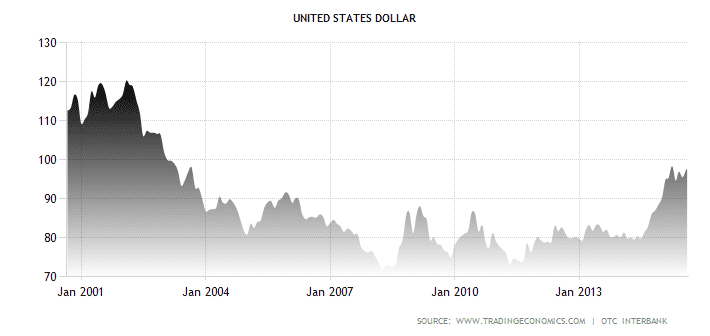

This creates a fault line for the global economy due to two factors. First there is the US dollar index, which has been rising as the Federal Reserve has signalled less accommodation and an imminent rate hike cycle – in contrast to every other major central bank. Policy divergence means a higher US dollar, causing emerging market currencies to hit a 15-year low and helping to precipitate a plunge in commodity prices. At the same time, China has a debt crisis to deal with and that necessarily means slower growth whether or not the losses associated with non-performing loans are socialized.

Now, the Chinese economy has been slowing for some time. I went back to my headline bookmarks and found a surprising number of headlines from as far back as 2012 pointing to slowing growth and stimulus to keep growth up. Here’s one from the Wall Street Journal from 2012, talking about growth slowing to 8.1%. And I would say that up until early 2014, the impact of this slowing was not acute as China was still gobbling up a record level of imported resources. But that’s exactly when the wheels started to come off and we saw our first mini-crisis in emerging markets.

In China itself, the debt burden has become unsustainable. With $20.8 trillion of additional debt, the country has accounted for more than one-third of total debt growth since 2007. The Chinese government is trying to work this problem out without precipitating a hard landing. And so the innovations are piling up. For example, Chinese-style QE is taking form with the People’s Bank of China putting money into state lenders that then go out and fund government-backed programs. Just recently, Chinese brokerages started an asset-backed security program that securitizes margin loans into exchange-traded securities. I think this will end badly but it doesn’t have to end catastrophically. We’ll just have to wait and see how it unfolds. Nevertheless, all of this is a way of lessening the pain as credit growth stalls as non-performing loans are written down. Growth will continue to slow as a result.

The result: China has become a major exporter of deflation worldwide.

Unrelenting Chinese prod price defl, w/ July -5.4%. Base lending rate 4.85%, real rate can’t fall fast enough. pic.twitter.com/5FFMsOrkjR

— George Magnus (@georgemagnus1)

The Chinese, tethered to a rising US dollar that is backed by policy divergence, are thus fighting against an appreciating currency even as credit growth slows. This necessarily means a big slowdown in import growth or an outright decline in imports and a slowdown in exports at the same time.

The reason commodity prices are declining is not just because of supply and currency, it is also because of demand. It’s about China’s disappearance as the marginal buyer of last resort. I believe the decline of China as buyer of last resort could well be an event of similar magnitude to the decline in the US in that role eight years ago. And I do not believe the Chinese will reverse this trend by pumping in enough stimulus to reverse the decline in credit growth. For economies leveraged to commodities and for non-US debtors indebted in US dollars, the advent of China as deflation exporter will be a very painful experience. In terms of crisis, I expect this combination of policy divergence and slowing growth in China to be the trigger. We are not there yet, especially since the US economy is growing. But the markers of stress and coming weakness – like a flattening yield curve in the US – are increasing.

Comments are closed.