Backside coronavirus responses after deep recession, equity rout

It’s increasingly clear that the coronavirus pandemic is going to cause a deep recession. And as retail investors understand the gravity of the situation, it will also cause risk assets to plummet, even from today’s levels. No, equities are not bottoming. In short, this Covid-19 outbreak will cause a bigger economic and financial crisis than the Great Financial Crisis did a decade ago.

What is the likely policy response to this? I told you in late February that the lockdown and quarantine approach was going to go global because this coronavirus outbreak was turning into a pandemic. The designation came on 11 March and the lockdowns soon followed. But, that’s just the initial policy response.

Now that we have seen lockdowns everywhere, increasingly, I have come to believe the economic pain will be too much to bear. Policy stimulus won’t be enough. And in the US at least, political wrangling will ensure it comes late. That means not just a deep recession but a global depression, something we haven’t witnessed since the 1930s. So, I am now looking through to the backside of the crisis when the lockdown and quarantine phase is relaxed. China, of course, is the first to go there. But, the economic pain Western democracies are willing to bear is likely less than China bore before the lockdown comes unstuck.

A global depression

A week ago, I took stock of my economic analysis in view of the deteriorating economic outlook. And here’s how I put it:

I am mostly happy with how quickly I recognized the downside risks of this pandemic. But I think it’s clear that I wasn’t quick enough. I simply didn’t recognize the magnitude of the threat. So, if I had to learn from that, I would ask myself today what reasonable worse case outcomes look like. And, unfortunately, the answers I come up with are pretty frightening…

At the time, I concluded that paragraph by saying: “So, actually, I’m not going to answer that question here so as not to spread panic. Instead let me focus on likely outcomes.” Now though, I think the time for soft-pedaling is over.

Look, every step of the way along the trajectory of this crisis, I have said most of the risk is to the downside. Nevertheless, I have outlined where I thought we were, pointing both to the reasons we could hope for the best and to the worst-case outcomes. For example, last Friday I ended by writing, “So there’s still hope that fiscal responses and central bank liquidity will prevent worst case outcomes from becoming realized.”

But, that’s just happy talk, frankly. I believe things are worse than that. While I have always hoped for the best, my ever-growing conviction has been that this is a crisis we (in the United States) don’t have the tools to fully mitigate. And now — with mass unemployment in sight, consumption ground to a halt, and politicians unable to even agree to supports an order of magnitude less than what’s needed — I am very much of the view that we are on the cusp of an economic depression and financial crisis.

Acting with conviction

So what do you do if you foresee an economic depression and financial crisis? This isn’t a purely academic question. I wrote a post over two weeks ago, asking “Are we in recession already?” And there, I said a recession “would mean a 40% down move in equities, base rates at zero and a 10-year yield approaching UK levels under 25 basis points. “

On that day, the S&P500 opened at 2954, down 13% from it’s highs. I remember listening to a financial advisor for an institution the very evening after I wrote the recession call. And he told me and my colleagues on the board of the institution I was involved with to stay the course. I warned that a recession meant 40% losses, i.e. big downside from where we were. But I wasn’t convinced enough of a recession then to argue forcefully to my colleagues not to heed the financial advisor’s advice. That was a mistake, because we have given up 22% since then. Had you re-balanced your portfolio back then, you would have avoided a lot of financial pain, perhaps even eked out some upside.

That was when I was talking about a recession. Now, two weeks later, I am talking about a Depression – and with more conviction and less hope than I spoke of recession two weeks ago.

Equities are going down from here, much further down. Here’s why.

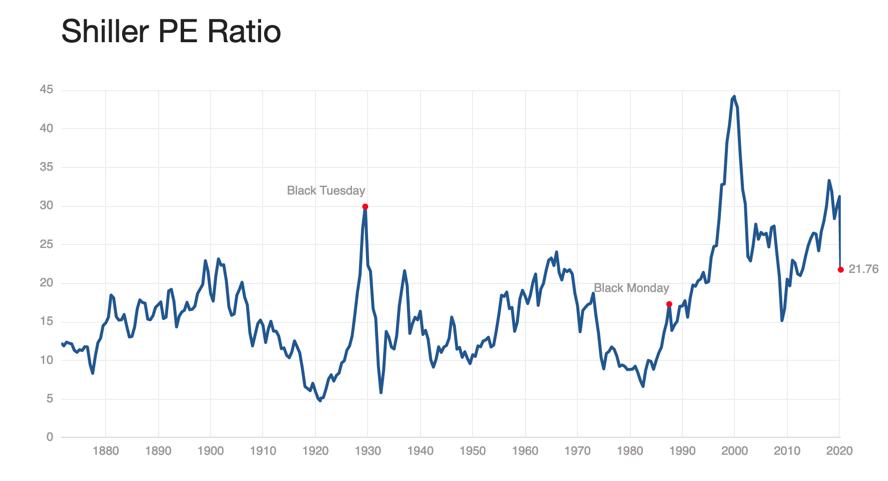

Equities are not priced for a depression, let alone a deep recession. If you look at the Shiller P/E ratio, the cyclically adjusted price-earnings ratio for the S&P 500, you can see shares are still at levels well above prior cyclical lows, with a Shiller P/E of almost 22 times earnings.

And when retail investors cotton onto this, they are going to follow the path of my neighbor I told you about on Friday. She has already gone to all cash. On Friday, I asked “How common has that been in this bear market?” And I said “I think it’s fairly common.” But, for a real bottom to form, it’s not common enough. When everyone starts in this direction, it causes markets to overshoot on the downside, as always occurs in a bear market. That will take shares much lower, with both earnings per share and the Shiller P/E falling.

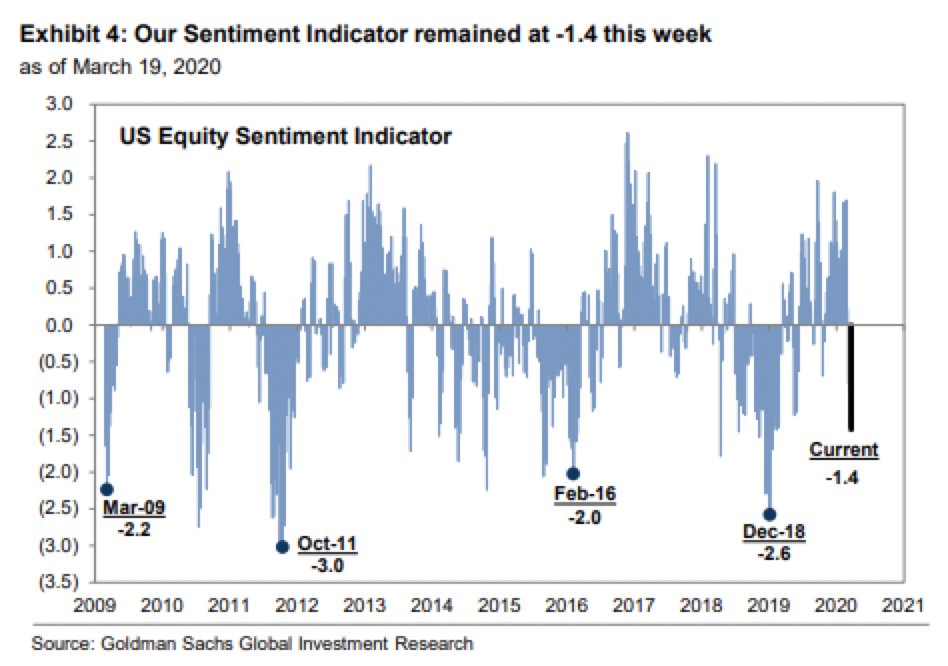

How do I know there are more investors to shake out? Look at investor sentiment. Here’s a chart from Goldman Sachs, for example. It tells you there is more downside to come.

And remember, that share buybacks have been a big part of the story during this present bull market, with earnings per share growing much faster than earnings. That’s gone now. And the lack of buybacks is another leg of support that will cause shares to fall.

More on the economy

Let me get back to why all of this makes sense. First, the numbers we are talking about here are of an order of magnitude greater than the Great Financial Crisis, perhaps our worst post-World War 2 recession. Here are some numbers.

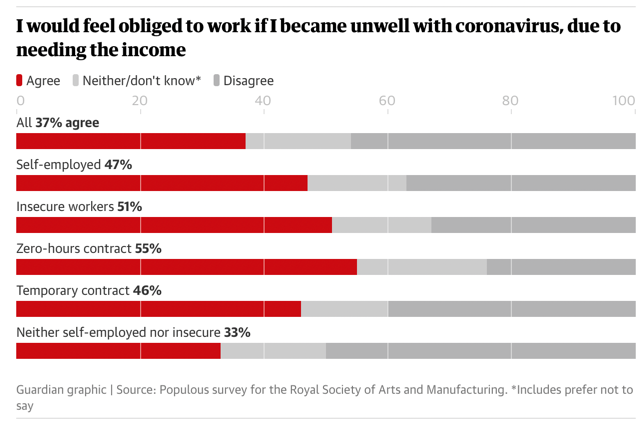

- Gig economy workers are facing a catastrophe – in the US and elsewhere. The UK Guardian reports that, on Friday, the Chancellor of the Exchequer “said self-employed workers could access £94.25 a week in universal credit, but he gave a far more generous deal to employees of 80% of salaries, capped at £2,500 per month.” That means they must work – even if they think they have coronavirus, something that will make the coronavirus pandemic worse.

- The hit to tourism and travel is enormous. Just yesterday, Marriott started its furloughs and Singapore Airlines announced a massive 94% of its flying capacity was being temporarily binned. At least 65 airlines have cut at least 95% of capacity.

- The collapse in demand caused oil prices to drop below $20 a barrel this morning for the first time since 2002. Many oil companies will go out of business. The rest will layoff tens of thousands of workers and cut capital expenditures as they hunker down. For example, Royal Dutch Shell announced overnight it was cancelling its buyback program (something I mentioned above) and that it was cutting capex from $25 billion next year to $20 billion or below. Multiply that by 100 times over — here’s a list of just some of the announcements — and you get a massive hit to consumption.

- Those are just a few examples of industries facing catastrophe. The result is that we are expecting over 2 million people to apply for unemployment benefits in the US alone — and for this week alone. To give you a sense of the scale, the US state of Michigan is seeing 21 times the number of filings this week that it has seen in recent weeks. It’s not far-fetched to think the unemployment rate spikes to 20% before this is over. St. Louis Fed President Bullard says it could even rise to 30% in the US.

- The knock-on effect is a crisis at the non-federal government level. States were already at risk of burning through those unemployment funds before the crisis. “Just last month, the U.S. Department of Labor warned that six of the nation’s largest states — California, Illinois, Massachusetts, New York, Ohio and Texas — would not be able to handle a surge in unemployment claims on their own. “

- Five US states have funded less than 50% of the costs needed to pay for their stated state public employee pension benefits. In 2018 I wrote that the Great American Pension Crisis is right around the corner. It has now arrived.

- Overall, economists at firms like Goldman Sachs, IHS and JPMorgan are talking about US GDP contracting at an annualized rate in excess of 20% in the next quarter – more than a 5% contraction overall. Though I think his number is extreme, Jim Bullard mentions 50% as a potential figure.

This is a catastrophe. It is a Great Depression scenario. I shudder to write this because I have always tried to understate the potential downsides, but a Depression has to be your base case here. That’s not the title of this post, again to avoid sensationalism. But, a Depression is my base case now.

Part of that goes to the knock-on financial crisis effects from the economic collapse. Certainly, we will get state and municipal government distress in the US and elsewhere. And the Federal Reserve will be forced to use the 2010 Blanchflower plan and buy up municipal bonds and monetize state debt. The Fed is already buying US federal debt and mortgage-backed securities. But it will have to add munis to that list too to prevent states and municipalities from collapse.

That won’t be enough though. There are sundry other markets that will face liquidity stresses as private sector bankruptcies pile up. I have mentioned some of these issues (see here and here). But, one area I mentioned really just once is commercial real estate. It will definitely be infected by the coronavirus, as will residential property when people can’t pay their mortgages. Thomas Barrack has a good article on how to stop this from becoming a catastrophe. It’s going to require massive government intervention as with everything else.

But, ultimately, how much intervention can governments get away with politically? That’s a real question because I don’t see western governments intervening any- and everywhere until a depression has set in. And, unless they do intervene aggressively, we will have a depression. There will be too many markets in crisis to realistically hope for any other outcome.

Backside policy response

I have been going through all of this in my head for a week or more now. And the conclusion, I have come to is that there are too many moving parts, too many broken markets to fix, for Western governments to avoid a depression… unless they jettison the lockdown and quarantine approach.

Already, I have been seeing analyses of this come out and they all make me feel uncomfortable, because basically, what we’re talking about here is a trade-off between human life and the economy. And what I told you a month ago is that human lives are so precious that, politically, there would be no alternative to lockdown and quarantine. But, once depression kicks in the calculus will change.

How many lives will be lost from a global depression? It’s hard to quantify something like that because there are lots of potential vectors – poverty, imprisonment, suicide, violence, and even war. But, from a political standpoint, as unavoidable as the lockdown was, the reversal of the lockdown will also be.

Let me give you an example of what I’m talking about. This is from David Katz, president of True Health Initiative and the founding director of the Yale-Griffin Prevention Research Center. The Yale-Griffin Prevention Research Center is one of 26 research prevention centers of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). So, these guys are all about public health. But, here’s what Katz wrote in a NY Times Opinion piece on Friday:

If we were to focus on the especially vulnerable, there would be resources to keep them at home, provide them with needed services and coronavirus testing, and direct our medical system to their early care. I would favor proactive rather than reactive testing in this group, and early use of the most promising anti-viral drugs. This cannot be done under current policies, as we spread our relatively few test kits across the expanse of a whole population, made all the more anxious because society has shut down.

This focus on a much smaller portion of the population would allow most of society to return to life as usual and perhaps prevent vast segments of the economy from collapsing. Healthy children could return to school and healthy adults go back to their jobs. Theaters and restaurants could reopen, though we might be wise to avoid very large social gatherings like stadium sporting events and concerts.

So long as we were protecting the truly vulnerable, a sense of calm could be restored to society. Just as important, society as a whole could develop natural herd immunity to the virus. The vast majority of people would develop mild coronavirus infections, while medical resources could focus on those who fell critically ill. Once the wider population had been exposed and, if infected, had recovered and gained natural immunity, the risk to the most vulnerable would fall dramatically.

A pivot right now from trying to protect all people to focusing on the most vulnerable remains entirely plausible. With each passing day, however, it becomes more difficult. The path we are on may well lead to uncontained viral contagion and monumental collateral damage to our society and economy. A more surgical approach is what we need.

Translation: We must lift the economy-crushing and indiscriminate lockdown and quarantine approach now, not just because it is killing our economy but because as he put it earlier in that piece:

Right now, it is harder, not easier, to keep the especially vulnerable isolated from all others — including members of their own families — who may have been exposed to the virus.

My view

To sum up here, we are now headed toward an economic depression and financial crisis because the global economy is collapsing. And the collapse is the expected outgrowth of an equally expected lockdown in response to the coronavirus pandemic. But, at some point, the economic pain will be too great to bear and people will begin to question the all-encompassing approach to thwarting viral contagion. And so, I expect this will force an earlier lifting of the lockdown and a move toward the more surgical approach David Katz is advocating.

What makes me uncomfortable is the thought that, in lifting the lockdowns, we would be choosing the economy over human lives. But Katz’s essay suggests that this may not be the right way of looking at the choices. And so that gives me reason for hope.

In the meantime, while the lockdown is in place, my expectation is for the global economy to deteriorate further, slip into depression and precipitate a financial crisis. I don’t write this cavalierly though. I know this is an extreme outcome. But, this is the path we are on. And there’s little evidence we will deviate from it in time to prevent economic collapse.

A 60% fall in equities is a base case then. And that means a retirement crisis for the baby boom generation and Generation X. And there will be hell to pay politically. The political fallout from this crisis will be just as severe as the economic fallout.

Comments are closed.