The Significance of Consumer Deleveraging

For some time it has been our view that the recent recession, unlike all other post-war recessions, was caused by a credit crisis, and that it would therefore be followed by a series of weak recoveries and frequent recessions until consumers successfully deleveraged their exceedingly heavy debt loads. That scenario now seems to be happening in accordance with our projections. A statistical economic recovery that was already far weaker than average has decelerated even further and the ECRI weekly leading indicator index strongly suggests that another recession may be in store.

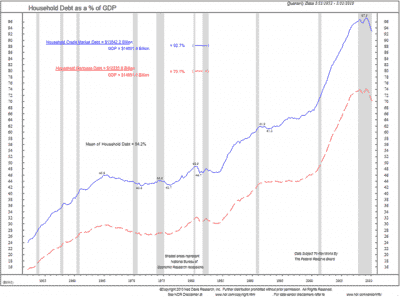

Consumers have only begun to cut back on their severe debt burdens, and the process will take a number of years. Household debt relative to GDP soared from a range of 43% to 49% in the 20-year period between 1965 and 1985 to a peak of 97.3% in 2009. As of March 31st (the latest data point) this dropped only slightly to 92.7%. To provide some more perspective, Ned Davis Research estimates the mean to be 54.2% over the past 58 years. The percentage climbed gradually to 65% in 1998, and then really accelerated to its recent peak.

To be conservative, let’s assume that the household debt/GDP ratio falls back only to the 65% level of 1998 rather than to the lower level between 1965 and 1985 or to the long-term mean. Under that assumption household debt would have to be pared back by about $ 4 trillion (from the present total of $13.5 trillion), an amount that constitutes about 40% of current consumer expenditures. While this could be accomplished over a number of years, it can readily be seen that the deleveraging would create a highly significant drag on consumer outlays for an extended period. Since such spending accounts for some 70% of GDP, this creates a serious drag on the overall economy as well.

As we expected, consumer spending has been weak despite the massive stimulus provided by the Fed, the White House and congress. In addition, with mortgage debt accounting for a majority of total household debt, the housing market has remained under pressure as well. The statistical economic recovery to date has been far weaker than the post-war average. Over the first four quarters of the so-called recovery GDP growth has averaged only 3.0% quarterly, compared to growth of 5.9% over the last nine recoveries from recession. Furthermore growth in the last quarter was only 1.6%, far under the average of 5.9% for the 4thquarters of previous expansions.

More recently the economy has slowed even more as indicated by data released over the last few months. This development has now been recognized by most economists. The consensus of economists has now reduced their projected growth rates for three consecutive months. The Fed Beige Book released yesterday referred to "widespread signs of deceleration". ISI’s Ed Hyman stated that their weekly company surveys "suggest slowdown is broadening and intensifying". Overall the economy seems in danger of slowing down to "stall speed", airplane terminology referring to the minimum speed necessary to keep from crashing.

Over the past week or so the market has been somewhat encouraged by a few indicators that came in above expectations. However, the data was still very soft, and merely indicated that the economy may still be growing at an extremely low rate. Moreover, these indicators are coincident with the economy at a time when the leading indicators with a good record of prediction are strongly suggesting the distinct possibility of recession.

For instance, last week the ECRI Weekly Leading Indicator was down 4.11% from a year earlier. We searched the historical data to determine what happened to the economy at other times when the index was down 4.11% or more year-over-year. Over the last 42 years this has occurred seven times, and in all seven instances a recession started shortly before or shortly after the signal. We also note that all of these instances were accompanied by bear markets in stocks. Although no indicator is certain in economics or stock markets, seven for seven is nothing to sneeze at. We note that ECRI Managing Director Lakshman Achuthan has not yet officially called a recession, although he has stated that, based on his index, there was more than a 50% chance of one.

In our view the market is in a volatile trading range that is part of a topping formation much like the topping process in early 2000 and late 2007. The trading range is likely to be violated on the downside when the economic recovery fails to accelerate and companies begin to bring down their revenue and earnings guidance.

Comments are closed.